This is a sample article from the September 2011 issue of EEnergy Informer.

A proposed law aims to kill two birds with one stone.

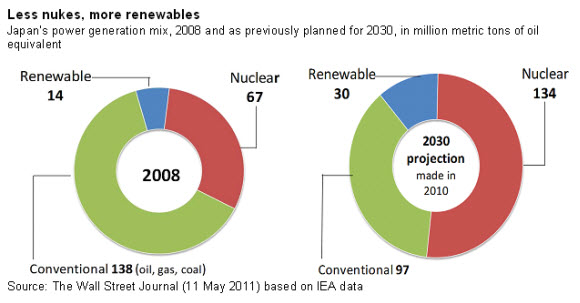

With no indigenous energy resources of its own, aside from renewable, Japan’s energy policy has been to rely on nuclear power for a growing share of its domestic needs, supplemented with imported oil, natural gas, and coal. Nuclear energy offered a second attractive attribute: low greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, especially if someone else does the mining and processing of the nuclear fuel. As one of first signatories of the soon-to-expire Kyoto Protocols, Japan has pledged to reduce its carbon footprint.

The policy was welcomed by Japan’s 10 major privately owned electric utilities, who are vertically integrated and have traditionally enjoyed a near monopoly hold on all aspects of electricity generation and distribution — a situation which has been slowly eroded in recent years with the arrival of independent power producers (IPPs). Continued reliance on nuclear power favored the status quo — who else could afford the massive investments in building new nuclear power plants if not vertically integrated utilities with captive customers — encouraged by supportive government policies?

Over the years, government policy, utility strategy, and the role of regulators in charge of nuclear safety became increasingly intertwined. For example, the regulatory agency in charge of Japanese nuclear safety was also promoting nuclear power with tacit government approval, prodded by Japanese utilities, who wished to maintain their monopoly and vertically integrated status.

The big earthquake and tsunami of March 2011 not only knocked out power to the Fukushima nuclear plant, but more important, exposed the cozy relationship that had existed between the regulator and the regulatee, long tolerated by the government. The result was the loss of public confidence in the nuclear industry as well as the standing of the Japanese nuclear safety and regulatory apparatus.

In mid August 2011, with the personal backing of the prime minister Naoto Kan, a landmark law has been introduced at the Japanese Parliament that, if passed, will kill two birds with a single stone. It will give a much needed boost to renewable energy and — more important — it will loosen the tight grip of the dominant utilities.

The law’s two main features are:

- The introduction of a basic feed-in-tariff (FIT), similar to those in use in Europe, for all qualifying renewable generation fed into the grid. The FIT would be set, and periodically adjusted by the Industry Ministry; and

- An obligation on utilities to buy what is offered at the set price.

Key features of the Japanese law have a vague resemblance to the Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA) passed by the US Congress in 1978. PURPA specified how much should be paid for power generated by non-utility generators — later known as IPPs — and obligated existing utilities to buy what ever was offered to them by qualifying facilities or QFs. PURPA’s FIT equivalent was called avoided cost.

Despite many shortcomings and uneven implementation in different states, PURPA eventually broke the monopoly hold of US utilities in power generation business and was instrumental in ushering in competitive wholesale markets, now dominant in many parts of the US.

With the passage of the law, Japan, which currently gets only 9% of its generation from renewable resources — mostly hydro, with some geothermal, wind and solar — may increase its reliance to 20% by early 2020s. If successful, it will allow a diminished role for nuclear power, reduce imported energy costs without increasing the country’s GHG emissions. If it further loosens the utility’s monopoly status, that would be the icing on the cake.

Mr. Kan, who is expected to retire soon, said he believes Japan will experience “explosive growth” in renewable generation. History may count it as his most enduring legacy.