Bifurcated future shows mature markets, and the rest of the world, diverging

This is a sample article from the February 2013 issue of EEnergy Informer.

ExxonMobil’s annual energy outlook, released in late December 2012, provides an educated view of the global energy supply and demand to 2040, albeit from the perspective of the world’s biggest listed oil major. Even though Bill Colton, Exxon’s VP for Corporate Strategic Planning claims that the report’s projections are not necessarily what Exxon would like to see, it would be foolish to assume that the oil giant is indifferent to what happens or, for that matter, can refrain from attempting to influence the outcome to its advantage. After all, there is a lot at stake for a company like Exxon who has invested billions in fueling the world’s voracious appetite for liquid fuels and gas.

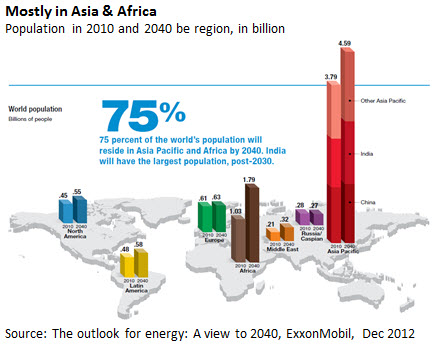

The fundamental drivers for energy demand are well-known, growing population — overwhelmingly in developing economies — growing income levels and growing aspirations of millions of people who will join the ranks of the lower and middle class between now and 2040 for higher living standards. A glimpse at global population projections (graph above) speaks volumes on what will drive global demand for energy; clearly it is not from the developed parts of the world.

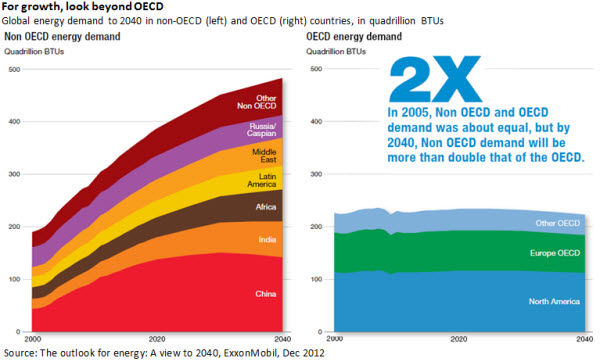

For oil majors like Exxon, Shell, BP, Total, as well as energy exporting countries like OPEC, Australia, Brazil and South Africa — to name a few — future growth markets are clearly outside OECD. The OECD demand, while substantial, is not projected to grow; contrast graph below on left for the former and on right for the latter.

Non-OECD energy demand, which is now roughly equal to OECD demand, will more than double by 2040 while OECD demand remains flat, or possibly drops modestly, depending on assumptions about economic growth rates, improvements in energy efficiency and, of course, energy prices. The same applies to developing countries, of course, but it is hard to imagine flat demand outside OECD no matter what assumptions are made. Population growth outside OECD, for example, is virtually guaranteed to continue to rise for several decades before it will plateau.

But a closer look shows other important developments. Combined energy demand in China and India — Chindia — for example, is projected to plateau somewhere in mid 2030s and shows a modest decline afterwards as these two countries reach the peak of their industrialization and urbanization (bottom two segments of graph above on left).

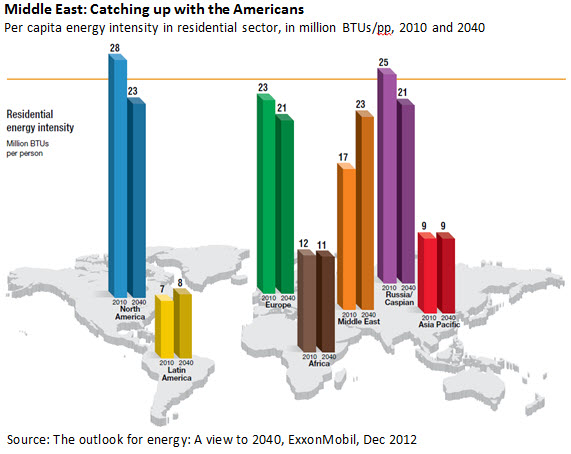

Middle East, historically seen as mere oil exporters to OECD, will evolve into major energy consumers. A number of current exporters will turn into net importers. By 2040, the average Middle Eastern citizen will use as much energy in the residential sector as in North America, slightly more than the average European — the latter two are projected to use slightly less on a per capita basis mostly due to continued improvements in energy efficiency (graph below).

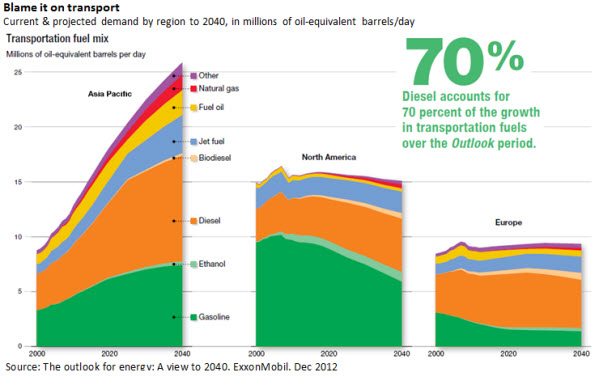

Oil majors have little to worry about, assuming they can find, process, refine, transport and retail liquid petroleum products for as long as the eye can see. While demand in traditional markets as in North America and Europe appear saturated and bound to shrink over time, the rest of the world shows no sign of reaching demand satiation, certainly not within the 2040 time period (graphs below).

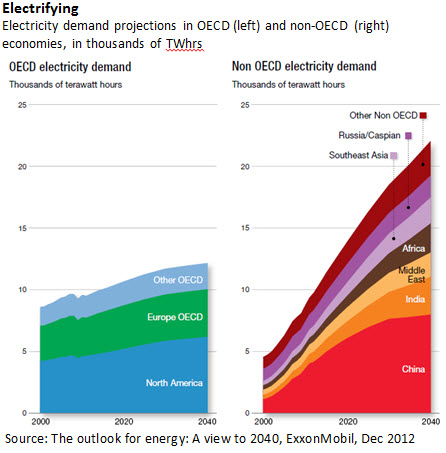

The same patterns are apparent in electricity generation sector, where little to modest growth is projected in developed economies while non-OECD demand shows no bounds (graph below). But even here, electricity demand in China is projected to plateau in 2030s.

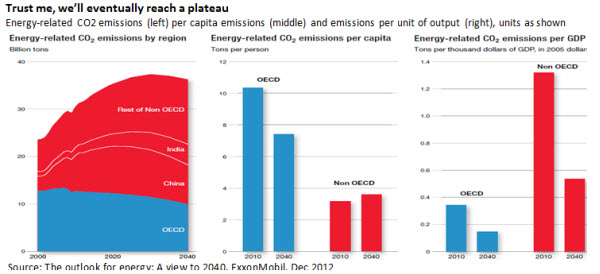

For those concerned about climate change, Exxon’s crystal ball suggests that one might expect a peak in energy-related CO2 emissions sometime in 2030s (graphs below). It shows OECD emissions on the decline, followed by the rest of the world. Clearly, the results will critically depend on assumptions about policy changes — say aggressive renewable targets — relative prices — say cost of renewable vs. conventional generation or adoption of carbon taxes — and other factors such as an international binding treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

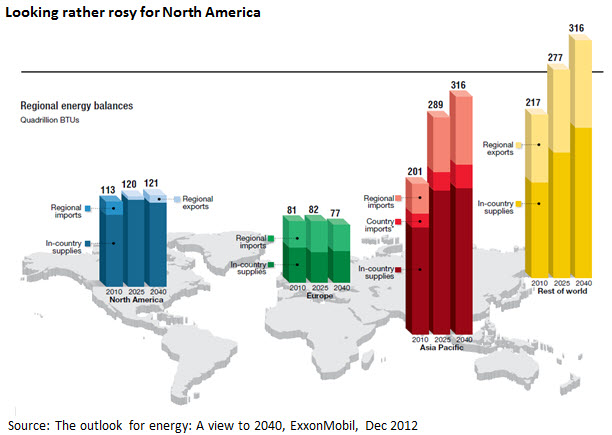

By now, it should come as no surprise to anyone that Exxon has joined the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration to predict that North America will become a net energy exporter by 2025 — the date varies somewhat depending on who is doing the analysis and the assumptions (graph below).

Unconventional natural gas production is among the reasons as is more efficient utilization of energy. Coal consumption, while remaining robust, will drop in relative terms assuming more natural gas at lower prices. Mature economies are projected to produce 80% more GDP while using the same amount of energy. Everyone has heard these before.

As observed in prior reviews of similar long-term projections of energy supply and demand produced by the likes of Exxon, these studies tend to take a hands-off, back-seat approach even though it is hard to imagine that the companies are indifferent to the outcome or mere bystanders in how the future unfolds.

What is lacking is a sense of purpose, or grand design — if there indeed is one — beyond finding and selling more oil and gas. While no motorist looks forward to a gas station with empty tanks, or with prices that are out of reach, shouldn’t a company with the size, resources, and clout of Exxon do more than merely trying to keep the gas pump from drying up?