This is a sample article from the March 2012 issue of EEnergy Informer.

Future of energy will be more efficient and more diversified, if we wait long enough.

For quite some time, BP has published its Statistical Review of World Energy, an authoritative historical record of how much energy and what kinds of fuels are produced and used, and where. Last year, for the first time, BP published a forward looking report and posted it on the company’s website, not knowing if anyone would take notice of it. Apparently 36,000 people downloaded the report. That was good enough for Bob Dudley, BP’s new CEO, who is featured in this year’s edition, released in late January 2012.

In the introduction to BP Energy Outlook 2030, Mr. Dudley, who replaced the former CEO after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, points out that the report’s predictions, which go to 2030, “is not necessarily the energy world we at BP like to see,” repeating a line from ExxonMobil’s similar report that goes to 2040, released in December 2011 and previously covered in this newsletter.

The storyline of the two reports, and similar annual outlooks coming out of the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Energy Information Administration (EIA), are broadly the same and follow nearly identical patterns. Even if there are no surprises, the pictures that emerge from the analysis are stunning.

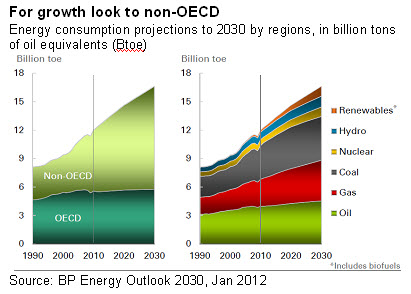

For example, under a business-as-usual scenario, overall energy consumption within the rich OECD block in 2030 is projected to be a mere 4% above the 2010 level. It is not hard to imagine alternative scenarios — for example one with higher oil prices and/or more stringent energy efficiency standards — that could virtually wipe out all growth from the OECD region. In this case, the increased growth of GDP, and population to the extent that it happens, can be more than compensated by improvements in energy intensity.

Even under the business-as-usual scenario, within some OECD countries, there is no discernible growth in energy consumption at all — this despite continued growth in GDP, and in some cases, population. The explanation: continued improvements in energy utilization efficiency or falling energy intensity — two sides of the same coin.

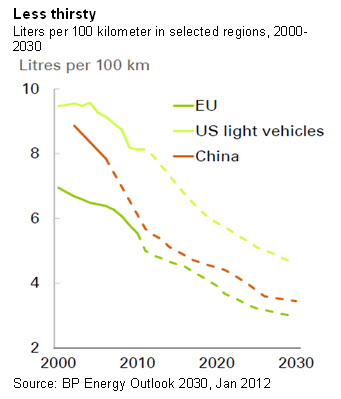

The result is that per capita energy consumption within OECD will actually decline over the next 20 years as will overall demand for transportation fuels. Late Lee Schipper, a transportation energy expert, was fond of referring to the latter phenomena as “peak transportation,” as in peak oil.

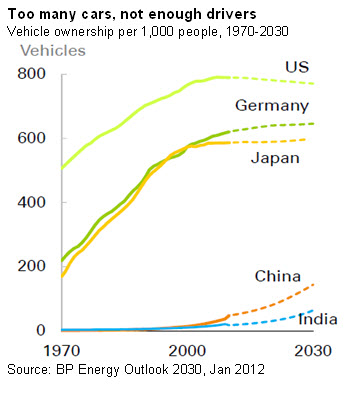

Clearly in a number of mature OECD countries, demand saturation is playing a contributing role, superimposed on gradual yet powerful energy efficiency and energy intensity trends. Car ownership in the US, for example, has peaked and shows a slight downward trend (see graph above right). Europe and Japan are not far behind. In the US, it simply boils down to not enough drivers for the number of cars sitting in the garages and in the driveways. In Japan, the problem is not having enough garages or driveways.

Even in developing countries like China, Indonesia, India or Thailand, getting a car is the easy part. Getting around congested metropolitan areas is a different matter. Yet anywhere one looks, cars, appliances, light bulbs, fridges, TV, pumps, motors, air conditioners, and everything else are getting more efficient over time.

Cars, a huge consumer of liquid fuels, for example, are universally projected to become less thirsty — and higher petroleum prices and dwindling fuel subsidies will accelerate the trend.

Commenting in the European Economic Review (19 Jan 2012) on the story behind the story, Christof Rhul, BP’s Chief Economist, talks about two powerful trends with important ramifications for the longer-term path of energy demand.

- First is the global convergence of energy intensity; and

- Second, is the gradual equalization of fuel shares.

On the first, Rhul points out that since the dawn of the industrial revolution, energy intensity “has differed widely across countries and regions,” adding, ‘but since the 1980s, we see massive and accelerating convergence across countries.” It has never been as low as it is today, and never have differences across countries been so small.

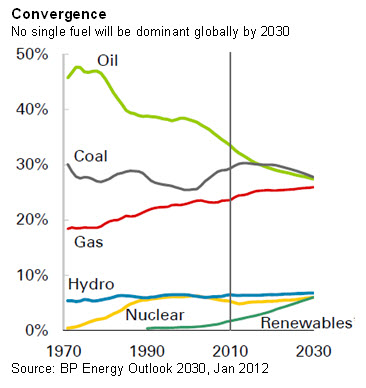

On the second trend, Rhul says that, “… for the first time since the industrial revolution, there will be “no single dominant fuel in 2030 — as coal and then oil used to be.” These two trends explain how the numbers “add-up” the way they do. Another way of putting is to say that natural gas grows, coal holds steady, oil falls, and renewables come of age so that by 2030 no single fuel is dominant.

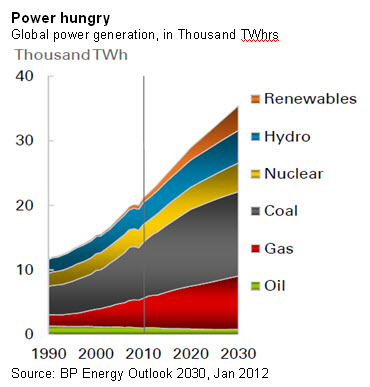

As developing economies mature, an increasing percentage of primary energy will be converted to electricity for final consumption, as has already occurred within OECD countries. This explains why 57% of global primary energy growth is driven by the growth of demand in the electric power sector (see graph below).

Nuclear, hydro and renewables account for 34% of growth in the power sector — where diversification away from the historical dominance of coal will be most pronounced. Yet, don’t expect any miracles any time soon.

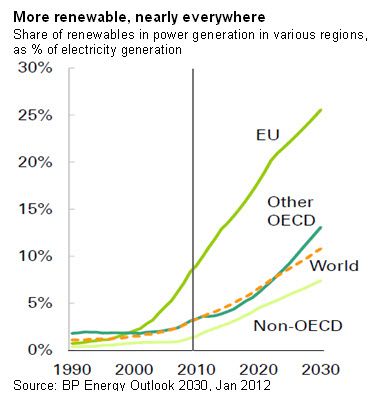

Renewable energy resources are projected to make significant contributions in meeting demand for electricity virtually everywhere, but notably within the EU, and to a lesser extent in other OECD countries. BP projects that in 2030, 11% of global power generation will come from renewables.

BP figures renewable resources will make up upward of 26% of power generation demand within EU by 2030 (see graph above). As impressive as this sounds, it is considerably below many other projections that put the renewable’s share as high as 50% within the EU by 2030. BP’s projections appear to be on the conservative side for Europe assuming a continuation of recent trends, and it is odd that BP does not explain or dwell on this important discrepancy with other forecasts.

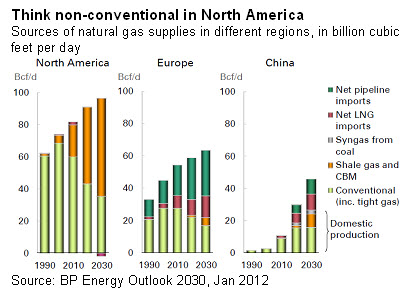

Among the stunning surprises of the past few years, of course, is the phenomenal growth of non-conventional natural gas particularly in North America, creating a supply glut and depressing prices to the point where some companies have decided to curtail future drilling because producing natural gas is no longer economic at current prices.

In January 2012, Chesapeake Energy Corp., the second largest natural gas producer in America, announced it was cutting back drilling in half in response to the depressed prices. Other companies are busy with plans to build LNG export terminals to ship the newfound gas to the Far East and Europe where it fetches much higher prices.

BP, like many others, is bullish on non-conventional gas in North America, projecting that it will account for more than half of total production by 2030 — from virtually naught in 1990. The picture is not so rosy for Europe or China (see graph above). Yet there are signs of increased drilling activity elsewhere, including in Ukraine, which has announced it will start exploration.

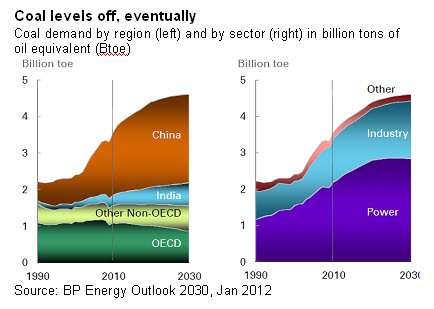

For those concerned about the impact of coal combustion on climate, there is good news and bad. The good news is that coal use will level off, eventually. The bad news is that eventually is some years away, and even then, coal will not go away, it merely won’t grow as fast as it would have under historical trends.

The two big culprits, as usual, are Chindia. Coal use is projected to decline within the OECD and is virtually flat in other non-OECD countries (see graph above). If climate change is to be averted, one needs to focus on China, and to a lesser extent, India.

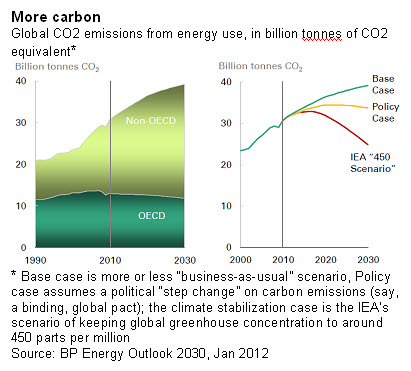

Why should anyone be concerned about climate change? Because the planet appears to be warming at an accelerating rate. And because scientists cannot find any other explanation other than human combustion of fossil fuels.

BP, like ExxonMobil and other oil majors — not to mention coal mining, exporting and consuming nations — merely pays lip service to the continued growth of greenhouse gas emissions. A single chart on page 80 of the 82-page report is devoted to the subject (below on right) — for political correctness, one assumes.

True, it is not BP’s fault, nor responsibility, to worry about global carbon emissions. But energy companies — producers and major users, including energy-intensive industries — must increasingly concern themselves with the implications of a warmer planet, and changing weather patterns, more severe storms and hurricanes, more severe and prolonged droughts and so on.

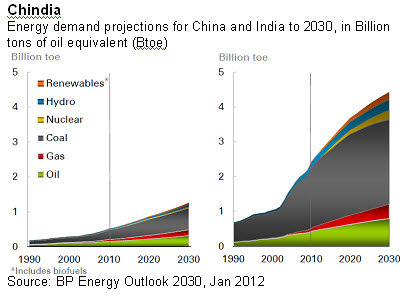

As repeated in nearly all studies of future of anything, China — and to a smaller extent, India — matters. These two countries, each with approximately 1.2 billion people, growing economies and a rapidly rising middle class, will not only influence the future course of global economy, but rather define it. One look at the projected demand for energy in Chindia (Figure below) is worth a thousand words.

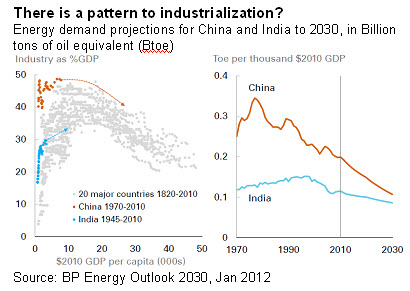

BP points out that countries have historically followed a predictable pattern as they industrialize and develop over time. As shown in graph below on the left, for 20 major developed economies from 1820 to 2010, the typical pattern is a sustained increase in industrial production as a percentage of total GDP, followed by a gradual decline as mature economies transition to the service sector, financial services and less energy-intensive industries, typically accompanied by increased per capita GDP.

China is already at the peak of its industrialization path, as the contribution from the industry to its total GDP appears to be on the decline. India, by contrast, has some ways to go before it falls into the pattern. Both countries, however, are on course to falling energy intensity, virtually converging by 2030.

Government policies on energy efficiency — as well as economic growth and energy pricing — will, of course, influence these patterns over time. Which is why policy matters.

In a paper titled How Will Energy Demand Develop in the Developing World? Catherine Wolfram, Orie Shelef, and Paul Gertler from University of California at Berkeley examine how demand growth in developing countries can be modified by various forms of intervention, such as more efficient appliances standards, cars, and buildings — something that is barely explored in the BP report.

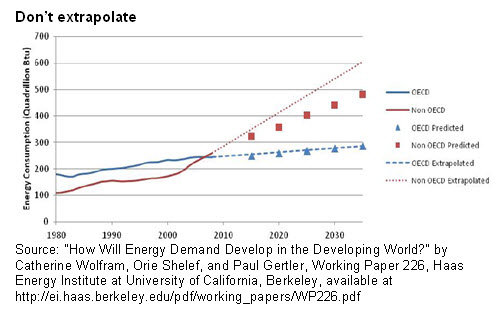

The authors suggest that future energy consumption at non-OECD countries, which is extrapolated to grow from roughly 250 Quadrillion BTUs or Quads today to upward of 600 by 2030, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), can in fact be modified downward.

Given that millions of the new middle class in emerging economies will be building new homes, buying new cars, and appliances, does it not make perfect sense that they somehow be encouraged to buy the most efficient varieties the money can buy?

It is broadly recognized that these first-time consumers generally buy the cheapest models on the offer – which means that they will be locked in with inferior products and infrastructure for which they will pay dearly over the life of the building, car or appliances.

As explained in an article on light emitting diodes (LEDs), a pricey LED light bulb will save $200 in lower energy costs — including its initial $40 price — over its long life, based on prevailing electricity costs in the US. The same principle applies in developing countries. The question is how to convince the poor to buy more efficiency instead of paying much more for the inefficiency?