Self-generation may be the disruptive technology that transforms utilities.

This is a sample article from the June 2013 issue of EEnergy Informer.

What started as a benign scheme to encourage homeowners and businesses to install rooftop solar PVs and other means to self-generate part of their electricity needs has grown — with astonishing speed — into a gigantic headache for the industry with the regulators caught in the cross fire. The scale of the self-generation business has simply grown too large and too fast to ignore. Yet the industry’s response to the threat appears lame — a classic case of too little, too late. Many observers, this newsletter’s editor included, believe this may be one of those disruptive technologies that may force the stodgy power industry to reinvent itself.

Net energy metering (NEM) started, as many things do, in California in 1996 with the passage of the first law of its kind. At the time, rooftop solar PVs were an expensive novelty for the rich and the environmentally committed, as were other forms of self-generation or distributed generation, usually defined as anything that meets some of a customer’s energy needs on the customer side of the meter.

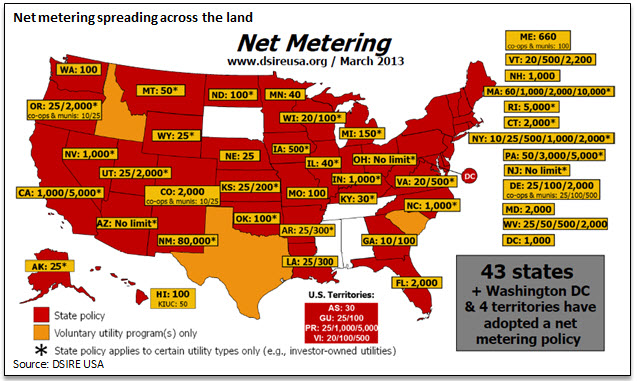

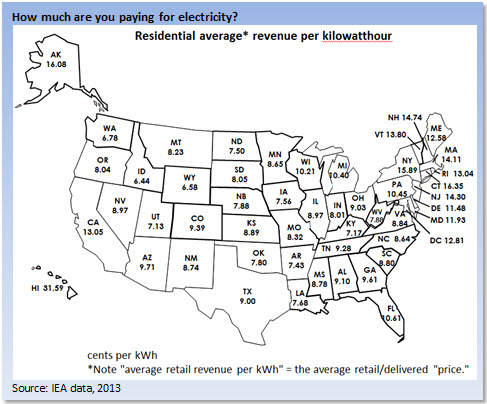

The original intent of NEM, as best as we can determine, was to encourage investment in distributed generation. The laws, now in effect in 43 states in the US — with similar schemes in Europe, Australia and elsewhere — typically obligate the utility to buy the excess generation from customers who invest in small-scale renewable energy systems, such as rooftop solar panels (map below). Because electricity storage is costly, customers typically sell the excess generation to the grid and buy back what they need from the grid at other times.

The clincher, which seemed innocuous at the time, was that customers would receive a credit on their bill for kWhrs sold to the grid at the same rate as what they pay when they buy kWhrs from the utility. Few regulators or utilities could have predicted how fast the scheme would take off and how ruinous its impact on the bottom line could be.

Depending on their usage and generation, many customers end up with zero or even negative volumetric consumption. For example, many schools in California end up with virtually no annual electricity bills because they produce a lot of electricity during the long, sunny summer months when schools are closed and there is no consumption. In this case, all generation is considered excess of demand, which means it receives a credit from the utility, wiping off the school’s consumption during overcast winter months. Not surprisingly, hordes of schools, hospitals, prisons, shaded parking lots, shopping malls, warehouses and office buildings are now covered with solar PVs.

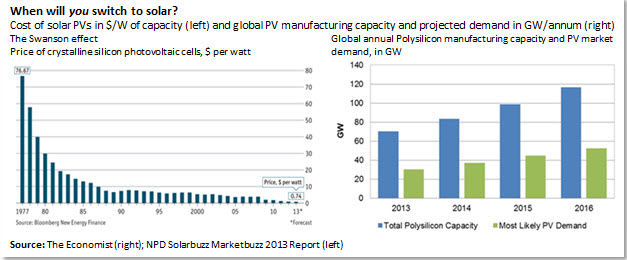

The problem, which started as a trickle has turned into a flood, especially in sunny parts of the country with high retail tariffs such as California. As the cost of solar panels fell and installers scaled up and learned how to market their products — for example offering to lease solar PVs rather than selling them outright which meant essentially zero money down — small-scale self-generation business took off.

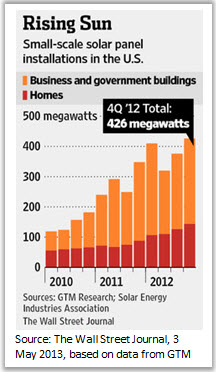

As shown in graph below, Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), a trade group, reckons there was over 426 MW of installed PV capacity in the US by end of 2012, from 100 in 2010, mostly in commercial and government buildings but increasingly in the residential sector. The numbers are currently negligible compared to the size of installed US capacity, over 1,000 GW, but the rate of growth has been remarkable. And that is what has alarmed the power industry.

What is alarming is that as customers began to switch to self-generation in increasing numbers, their gains – buying fewer net kWhrs from the grid and paying diminishing bills — meant that their neighbors had to pay more to make up the difference. Utility business, aside from fuel costs and some operating expenses, is essentially a fixed cost enterprise. When lots of kWhrs are sold, and sales are growing, the fixed costs can be spread among more kWhrs, reducing per unit costs. That, more than anything else, has been the industry’s golden rule since the days of Thomas Edison.

All of a sudden, the modern day Thomas Edison’s who run today’s power companies are confronted with a hard to ignore disruptive technology that is growing fast and is threatening their basic means of collecting revenues — mostly through a flat retail tariff applied to volumetric consumption. If volumetric consumption is flattened — say, because of increased investment in energy efficiency — or begins to fall — say, because of wide-spread popularity of self-generation — the industry may go into a tailspin or begin a slow and painful financial hemorrhage.

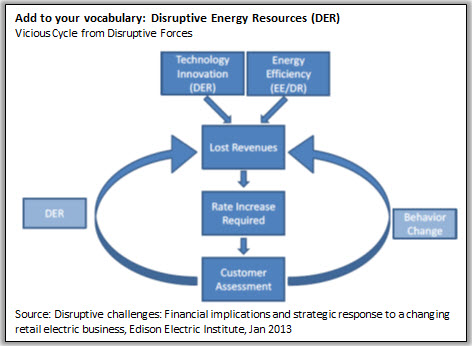

In case you think the seriousness of the issue is exaggerated, a recent report by the Edison Electric Institute, the lobbying arm of the investor-owned US utilities, concluded that the growth of small-scale solar systems represents the “largest near-term threat” to the industry (schematic below). To stop the menace, the institute recommended its members — who account for roughly 70% of the kWhrs sold in America — to change net-metering laws before it is too late.

It may already be too late. The solar lobby, while no match for the powerful utility lobby, is supported by millions of large and small consumers who like the idea of watching the meter spin backwards, metaphorically speaking, since spinning disk meters are becoming history. Net energy metering laws, like any form of energy or fuel subsidy, are highly addictive. Once a neighbor puts on the solar panels on the roof and gloats about his vanishing utility bills, everyone on the street wants them on their roofs — and state level utility regulators won’t be popular if they stop or modify the prevailing NEM regulations. There is intense public pressure to support renewable generation and clean PVs.

The Edison Electric Institute’s report points out that unless utilities act quickly the growth of solar power and small-scale power generation could make customers “electric grid independent.” Noting that many people no longer have landline phones — for younger generation those are phones physically connected to the wall with a hard wire, so you cannot walk away with them — the report asks, “Who would have believed 10 years ago that traditional wire line telephone customers could economically ‘cut the cord’?” It is a frightening scenario.

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal (3 May 2013) refers to a number of cases in states including California, Arizona, and Idaho on what to do about NEM before the issue of lost revenues gets even more out of hand. The article focuses on a contentious fight between Entergy Corp and NRG EnergyInc. in Louisiana — a state where rooftop solar PVs have negligible penetration and where retail rates are modest by US standards (graph below). But even in LA, where nothing happens fast, the rooftop PV capacity has gone from 50 kWs in 2008 to 4,300 kWs in 2012. Extrapolating that growth rate over the next few years is apparently what has scared Entergy Louisiana, which is a subsidiary of New Orleans based Entergy, among the largest investor-owned US utilities.

In comments to the Louisiana Public Service Commission (LPSC), Entergy points out that homes with rooftop solar aren’t paying their fair share of costs like maintaining power lines and responding to hurricanes, even though the solar homes still need the traditional electric grid when the sun isn’t shining, according to the WSJ article. If solar customers don’t pay enough, other customers have to make up the difference. Phillip May, the company’s CEO notes that the NEM scheme shifts “costs from net-metered solar customers … to customers who cannot afford to or choose not to generate their own power.” It is a matter of fairness and equity in allocation of costs and benefits, says Mr. May, with justification.

The staff of LPSC bought the argument, suggesting that Entergy be allowed to adjust the payment scheme to net-metering customers. According to the WSJ article, the basic idea is that instead of crediting NEM customers a dollar on their bill for every dollar of electricity their solar panels produce, they receive a smaller credit and/or pay a fixed charge to recover the costs associated with maintaining the grid and providing backup service.

Referring to the LPSC staff’s recommendation, Mr. May said the proposed rule change is “intended to put solar net metering in Louisiana on a more sustainable path going forward as its rapid growth continues.” Similar proposals are under consideration in a number of states in the US, including the PV front-runner California.

Not surprisingly, the solar PV industry, manufacturers, installers, and millions of prospective customers are aghast. Just when things were begging to pick up, they say, utilities are trying to put on the brakes. Lyndon Rive, CEO of solar developer SolarCity Inc., one of the big players, is justifiably concerned that utilities view distributed solar generation as a threat, which they do. “The amount of solar that’s deployed in Louisiana is insignificant. What they (utilities like Entergy) are trying to do is kill it (NEM and solar PVs) before it starts,” he is quoted in the WSJ article.

Commenting more broadly, NRG’s mercurial CEO, David Crane, recently called the traditional US utilities “an industry of Neanderthals,” adding it has been “the least innovative industry in America, maybe the world, in history.”

The stodgy, protected and slow changing utility business justifiably seems Neanderthal to outsiders. At issue, however, are developments that are likely to force fundamental rethinking of an outdated business model. In this context, the Neanderthals who wish to survive must ask themselves:

- What is the product or service that customers want and value the most – for those who buy zero net kWhrs it is clearly not the kWhrs anymore; and

- How should customers be charged for what they value, if it is not kWhrs?

In the case of self-generation and NEM, what zero-net energy customers need and want is reliable grid connectivity — and the services that comes with it — namely the ability to use the grid as a storage medium to dump excess generation when available and draw from the grid electricity at other times, 24/7. This is a valuable service for which NEM customers, except those who are entirely off-grid and self-reliant, should be willing to pay. So far nobody has bothered to explain to them why they should pay for being connected to the grid even if their net volumetric consumption is zero. It won’t be easy.

A fixed charge for merely being connected to the grid seems like a reasonable solution, as is a differentiated price for what is sold to and what is bought from the grid, based on the time of the transaction and its cost causality. Parallels from other industries, mobile telephone business in particular, should prove valuable.

Neanderthals did not survive evolutionary change; will today’s utilities do better?